Understanding the Teen Brain:

How Brain Development Shapes Behavior

Brain-Based Tips for Parents from My ACSW Presentation on the Adolescent Brain

I’ve had the opportunity to develop a workshop on the neuroscience of the adolescent brain, and it has been a fascinating journey. My goal is to help educators—and ultimately parents—understand, in clear and simple terms, why teenagers who are bright, caring, and capable sometimes make decisions that feel reckless, impulsive, or confusing.

My core message is straightforward: when we view adolescent behavior through the lens of a developing brain, conflict decreases. Understanding what’s happening neurologically can ease tension between parents, teens, and even clinicians. It also helps strengthen connections and makes it easier to navigate the many stressors adolescents face, including physical and hormonal changes, social pressure, academic demands, and emotional overwhelm.

This blog introduces some of the ideas I share in my workshop, but it is written especially for parents who feel frustrated, exhausted, confused, or at their wits’ end.

If that’s you, thank you for being here. Your willingness to pause, read, and stay open is already a powerful first step.

The Adolescent Brain Is Still Developing

We now know that the brain does not fully mature until the mid-20s. Some research even suggests that constant technology use may slow parts of this process. But what does this actually mean for your teenager?

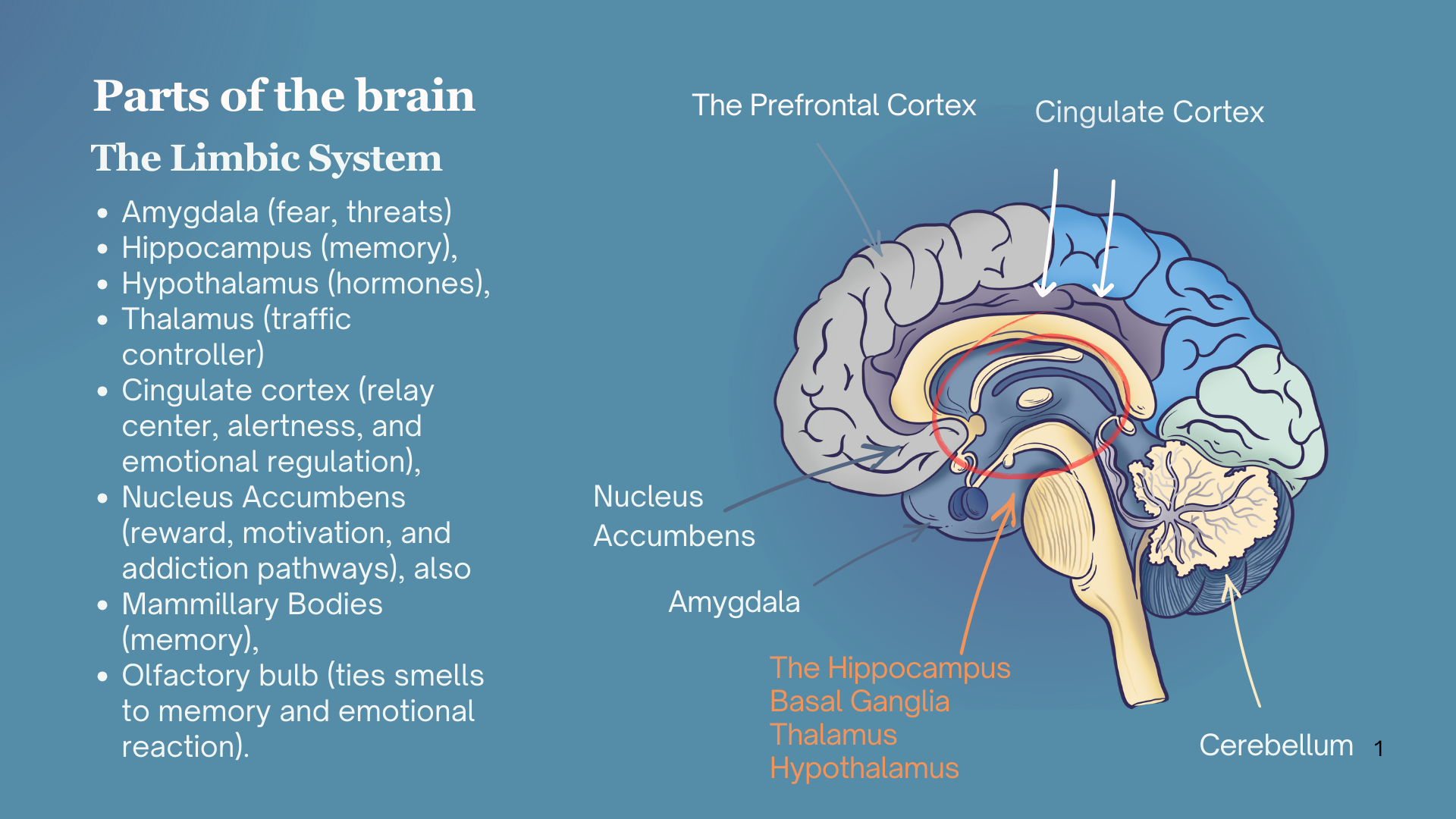

One key reason many adolescent behaviors are difficult to understand is that, during this developmental stage, the primitive, emotion-driven regions of the brain are more developed and more active than the prefrontal cortex. The primitive brain focuses on survival, emotion, and reward. It pushes teens toward novelty, excitement, and intense experiences because that’s how learning and growth occur at this stage.

The prefrontal cortex, which supports judgment, impulse control, planning, and emotional regulation, is still under development. As a result, adolescent behavior is often guided more by instinct and emotion than by careful reasoning. In practical terms, the “engine” of the brain is powerful, while the “brakes” that help slow things down are not yet fully installed.

This imbalance helps explain why teens may react quickly, take risks, or struggle to pause and think through consequences. These behaviors are not signs of defiance or poor character - they are predictable outcomes of a developing brain.

A Simple Example

Recently, I was on vacation with my children and grandchildren, and we attended a karaoke event open to all ages. As my grandchildren watched others perform, they became excited. My granddaughter ended up getting on stage with her mother and singing.

I was incredibly proud of both of them, but what stood out to me was this: my granddaughter didn’t hesitate. She didn’t stop to wonder what people might think, whether she would sing well, or whether she might feel embarrassed afterward.

Her brain hasn’t yet developed the inhibitions that many of us as adults carry. That same lack of inhibition that worries us in adolescents is also what gives them courage, creativity, and willingness to try. As adults, our fully developed prefrontal cortex often holds us back with fear and self-doubt. Teens haven’t built those brakes yet.

Stress, Survival, and Emotional Overload

It is also important to recognize that the adolescent brain is more sensitive to stress and perceived threat than the adult brain. Teens are responding not only to what is happening in the moment but also to how their nervous systems interpret safety, danger, and belonging. With regulatory systems still under development, stress can escalate rapidly and feel more intense for adolescents.

When a teen enters fight, flight, freeze, or fawn mode, the prefrontal cortex - the part of the brain responsible for reasoning, judgment, impulse control, and perspective - temporarily goes offline. This isn’t a choice. It’s a biological response.

This is survival mode.

In survival mode, the brain is focused on one thing: “Am I safe right now?” When safety feels threatened - emotionally or physically - the brain prioritizes protection over learning. That’s why moments of high emotion are not the right time for lectures, logic, or consequences. Even well-intended advice can feel overwhelming or threatening when the nervous system is dysregulated.

Adolescents already experience frequent emotional ups and downs due to physical growth, hormonal changes, identity formation, and heightened awareness of social belonging. When academic pressure, extracurricular demands, work responsibilities, social media, and family stress are added, students' nervous systems can easily become overloaded. When trauma, chronic stress, or instability is part of the picture, these responses tend to be stronger and last longer.

This is why behavior that looks like defiance, shutdown, or disrespect is often a signal of dysregulation, not disobedience. It’s a nervous system asking for help regulating before it can return to thinking, learning, or problem-solving.

When adults respond first with calm, predictability, and connection, they help the teen’s nervous system settle. Only after regulation returns does guidance, accountability, or problem-solving begin to make sense.

Why Teens Turn Toward Peers

Many parents are concerned when their adolescent begins to prioritize peers over family. While this shift can feel painful or rejecting, it’s actually a normal and necessary developmental step.

Humans are wired for connection and belonging. During adolescence, the brain naturally turns toward peers as a way to practice independence, social skills, and identity formation. This isn’t about abandoning family, it’s about learning how to belong to a wider world.

When parents stay emotionally available and connected, teens are more likely to return to the family as a secure base.

What Teens Actually Need from Adults

So what can parents, caregivers, coaches, and teachers do—especially if they don’t have clinical training?

It starts with this idea: adults can serve as a “borrowed prefrontal cortex.”

That means offering calm, predictability, and emotional containment when your teen’s brain can’t yet do that on its own. I always encourage connection and calm before correction. When a teen is dysregulated, reasoning and consequences won’t land.

Rather than complicating this with endless strategies, here are a few core principles:

1. Create safety - or improve the safety of the environment you already have.

2. Model emotional regulation. You are your child’s most powerful teacher, even in the limited hours you share each day.

3. Build connection. The most important goal is being the person your teen comes to with questions or concerns.

4. Maintain hope and teach problem-solving. Help them think through challenges instead of fixing everything for them.

Most teens don’t want solutions right away. They want to be heard.

“I knew I was finally becoming the kind of parent my teen needed when I stopped taking everything they said personally and started becoming compassionately curious about what they were really trying to communicate.”

Reframing Behavior Changes Everything

When we understand adolescent brain development, it changes how we respond. Curiosity replaces control. Coaching replaces punishment.

You will still lose patience at times. That’s not failure - it’s human. What matters most is repair. Apologizing, reconnecting, and modeling accountability teach far more than perfection ever could.

Remember, your long-term goal isn’t just getting through this season. It’s helping your child develop values, skills, and habits they will carry into adulthood. Teens who feel understood are far more likely to internalize those lessons.

Conclusion

When we shift from asking, “What’s wrong with teens?” to “What’s happening in their brains, and how can we support them?” we move from judgment to strategy. This shift allows us to respond developmentally rather than emotionally, changing not only how we interpret teen behavior, but how we show up as adults.

As frustration gives way to understanding, and control gives way to compassionate leadership, we begin to see that teen behavior isn’t broken—it’s developing. With a clearer understanding of the adolescent brain, adults become steadier, more effective guides. And when we lead with empathy and curiosity, conflict decreases and connection strengthens.

I encourage you to continue learning through this blog, trusted resources, and thoughtful conversations with professionals. Information is power. Understanding the adolescent brain may not make parenting easier, but it removes much of the unnecessary conflict and helps parents respond with greater clarity, confidence, and care.

Next week look for

Quick Tips for Parents of Adolescents: Brain-Based Guidance You Can Use Today

And coming soon, a downloadable handout you can share

I hope you find this information helpful. However, I must also mention that the advice given is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to diagnose or treat any condition. I always recommend that you consult with a licensed professional in their field of expertise.

If you believe this article will benefit someone else, please share it and email me if you have a topic you would like me to address. The email address is linked above.

If you found this topic interesting, you may want to explore one of the following blog articles.

Disclainer

The content on this website is for informational and educational purposes only. It reflects my personal and professional experience as a licensed social worker, but is not a substitute for therapy, counseling, or professional mental health treatment.

If you are struggling or need individualized support, please seek help from a qualified mental health professional. If you are in crisis or concerned for your safety, call or text 988 in the U.S. to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, or contact your local emergency services.